Keywords: media , advertising , brand , branding , brands , government , irrational media , law , propaganda , rational media , trademark , trademark law , trademarks , word , words

Whenever we say something we are in essence re-contextualizing the words we use in order to express our own expression. Words have been used since time immemorial. Ben Franklin had a self-imposed guide-rule to imitate Jesus and Socrates. Similarly, I wish to imitate Shakespeare insofar as I am time and again prone to invent new words, and perhaps I am also prone to use someone’s words and to transport them into different contexts. I do not wish to thereby alienate their meaning, but rather to consider whether their meaning also has implications outside of the contextual box they were originally “thought up” in.

Case in point: a statement Joe Rogan recently made about a more-or-less specific, contained topic — yet which was also embedded in a lengthy discussion about changes apparently currently occurring in the so-called “media” landscape [1]:

In my humble opinion, every utterance (or communication) created by anyone needs to be interpreted from at least two contextual perspectives:

- the language that utterance / communication is expressed in [2]

- The legal environment that utterance / communication exists in [3]

One example which is often viewed as a hallmark event which has separated modern history from previous eras is Martin Luther’s nailing the so-called “95 Theses” to a (Roman Catholic) church door in Germany. In order to interpret this document, we must consider not only the language in which its expression was written but also the legal environment in which it was expressed. This act (commonly attributed to Martin Luther alone) is usually interpreted as the seminal act that set off the Protestant Reformation and thereby sparked numerous revolutions not only throughout Europe but indeed globally for centuries to come.

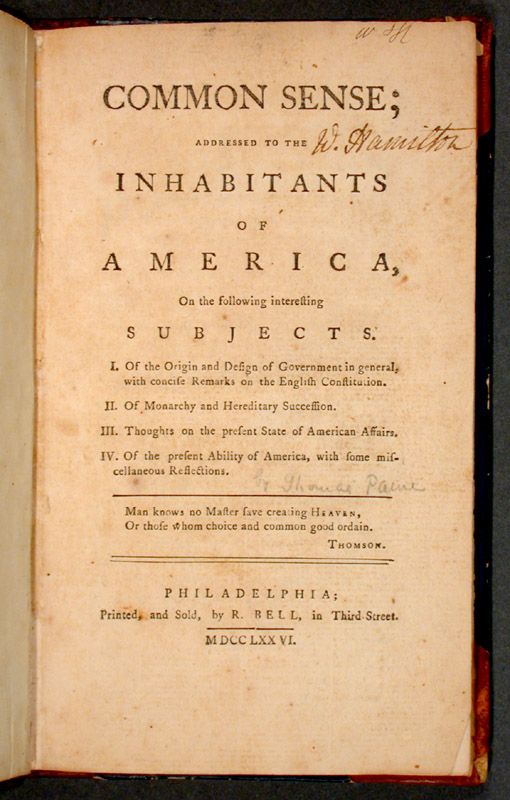

One such revolution was the so-called “American Revolution”, which happened well over two centuries later — and in a different legal environment — namely one in which the aforementioned Ben Franklin published Tom Paine’s “Common Sense” pamphlet, in which Mr. Paine argued that “In America, law is king”.

In the meantime, the world has become immensely more complex, and the notion of “Natural Law” which existed in Revolutionary America is now a quaint and antiquated relic of an entirely different legal environment than the legal environments which exist worldwide today. Today’s legal environments are immensely more diverse and multifaceted, they overlap in layers upon layers of legalese, such that the entire global legal environment is neither completely intelligible nor individually fathomable for any mere mortal human being (I even doubt that one lifetime would suffice to even read all of the relevant legal documents anywhere, let alone to begin to grok them).

What the world needs most of all now (again: in my humble opinion) is to simplify. Our new millennium ought to become an era of stepping back from legal documentation, and moving forward to interpersonal understanding. Now, more than ever, we need to look each other in the eyes and work towards mutual understanding.

Lastly (for now — and yet again in my humble opinion) this pretty long plea is probably much easier said than done. Yet even the longest and most difficult trip begins with taking the first step … and I have a hunch that first step may very well have something to do with us engaging in a collaborative attempt to subscribe to each other’s views, with not giving up and instead remaining steadfast, persistent, engaged and diligently working towards the intermediate goals we choose to focus on in order to help us achieve our dreams of lasting success.